Vectors, Linear Combinations, Span and Basis

On the previous page, we defined a vector space from a mathematician’s perspective. While that definition is precise, it’s quite abstract and doesn’t do much to build intuition for the machine learning algorithms we’ll explore later. Here, we’ll take a more concrete approach, while also introducing some basic—but important—concepts that come directly from the definition of a vector space. Let’s start with vectors.

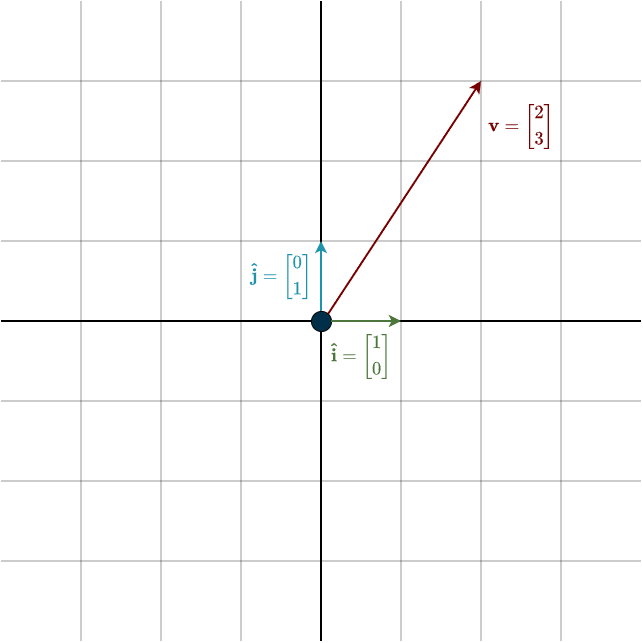

Visualizing Vectors

We’ve described vectors as lists of numbers, where both the order and length of the list matter. Typically, vectors are written using a bold letter, like \(\mathbf{v}\) and with brackets. For example, if we’re working in 2-dimensional space, meaning our vector space is \(\mathbb{R}^2\), an example vector might look like this:

\(

\mathbf{v} = \begin{bmatrix}

2\\

3\\

\end{bmatrix}

\)

or generally:

\(

\mathbf{v} = \begin{bmatrix}

v_1\\

v_2\\

\end{bmatrix}

\)

with \(v_1, v_2 \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(\mathbf{v} \in \mathbb{R}^2\).

In some textbooks, a vector might also be written in a single line like this: \(\mathbf{v} = (v_1, v_2)\). This is the same list notation we saw on the previous page, both notations mean the same thing. One important point is that we will always treat vectors as column vectors. We’ll see later why this is important. So, whenever you see a vector, especially in the context of machine learning, just assume it’s a column vector. Note that even when a vector is written in list notation on a single line, it still refers to a column vector.

Now, let’s move on to drawing a vector. It’s essentially the same as the picture on the previous page, except that you’ll connect the point described by the coordinates with an arrow, starting from the origin (the point where the axes meet). Vectors are almost always drawn starting from the origin.

On the previous page, we used the number line to understand what coordinates like 2 or 3 mean, and we knew exactly where to place them. Now, it’s slightly different. Instead of reading the coordinates off the number line, we simply move 2 units to the right and then 3 units up. But what does it mean to move to the right or up? Specifically, we take a certain number of these other vectors, marked in green and blue, which indicate our direction. We scale the green vector by 2 and the blue vector by 3. Mathematically, this means we use scalar multiplication, where the scalars are the coordinates of the given vector:

\(\mathbf{v} = v_1 \cdot \mathbf{\hat{i}} + v_2 \cdot \mathbf{\hat{j}} = 2 \cdot \mathbf{\hat{i}} + 3 \cdot \mathbf{\hat{j}}\)

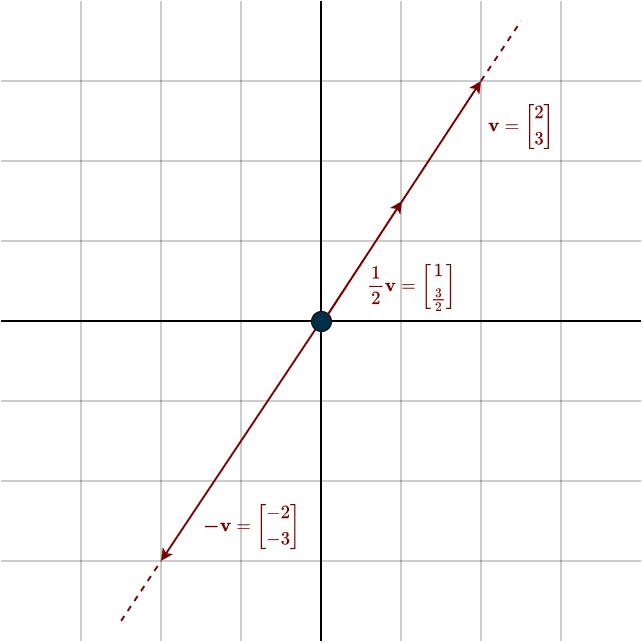

But what does scalar multiplication look like geometrically?

Scaling Vectors

Multiplying a vector by a scalar changes its size and possibly its direction (geometrically speaking). If the scalar is greater than 1, the vector becomes longer. If it’s between 0 and 1, the vector shortens. If the scalar is negative, the vector flips direction. We call it a ‘scalar’ because it scales the vector. It’s important to note that while a scalar can stretch, shrink or flip a vector, it can’t rotate it—rotation isn’t possible through scalar multiplication alone.

We defined scalar multiplication mathematically on the previous page, but just to refresh your memory, it simply means multiplying each entry of the vector by the scalar. You can also see the additive inverse visually here \(\mathbf{v} + (-\mathbf{v}) = \mathbf{0}\). The two vectors cancel each other out, leaving only the zero vector, which is located exactly at the origin. Speaking of which, what does vector addition look like visually?

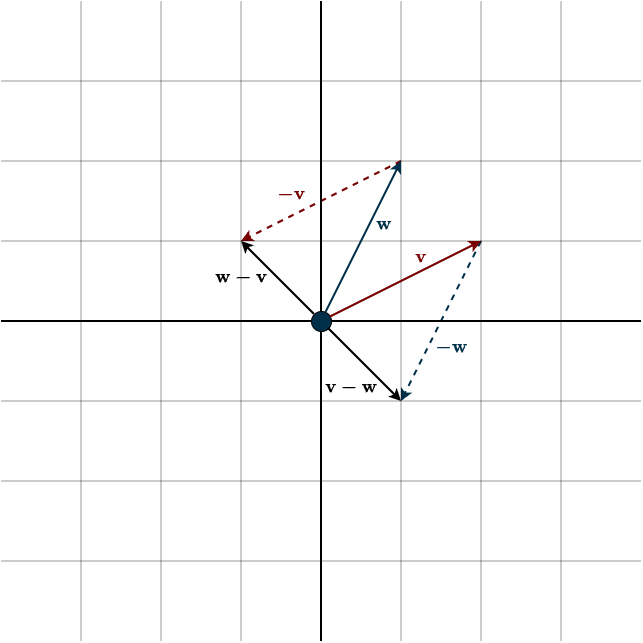

Vector Addition

Adding two vectors geometrically is straightforward. This is one of the few cases where you move a vector away from the origin. You simply place the tail of one vector at the head of the other. The order doesn’t matter, the result is the same, because vector addition needs to be commutative.

Subtraction requires a bit more attention. As we saw on the previous page, subtraction is really just addition with additive inverses. However, it’s important to note that \(\mathbf{v}-\mathbf{w}\) and \(\mathbf{w}-\mathbf{v}\) are not the same, since \(\mathbf{-v}\) and \(\mathbf{-w}\) are different. It’s also interesting to point out that the additive inverse of \(\mathbf{v}-\mathbf{w}\) is \(\mathbf{w}-\mathbf{v}\) (since \(-(\mathbf{w}-\mathbf{v}) = -\mathbf{w} + \mathbf{v} = \mathbf{v}-\mathbf{w}\)).

Next, we’ll introduce a new concept that follows directly from the definition of a vector space.

Linear Combination

By adding vectors, we create new vectors, which follows from the closure property of a vector space. This means we can write some vector as a combination of other vectors. Looking at the image above, we can call the resulting sum vector \(\mathbf{x}\) and describe it like this:

\(\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{w}\)

We call such a combination a linear combination. So, \(\mathbf{x}\) is a linear combination of \(\mathbf{v}\) and \(\mathbf{w}\). Now, let’s look at it more generally:

A linear combination of a list \(\mathbf{v}_1, \dots, \mathbf{v}_m\) of vectors in \(V\) is a vector of the form:

\(a_1 \cdot \mathbf{v}_1 + \dots + a_m \cdot \mathbf{v}_m\)

where \(a_1, \dots, a_m \in F\).

Notice again that our field is \(\mathbb{R}\), so the definition above simply means we take multiples of some vectors and add them together to create a new vector. It’s called a ‘linear’ combination because the scalars are linear. Now, here’s the interesting part: given two vectors, there isn’t just one combination you can create, but infinitely many. Consider this:

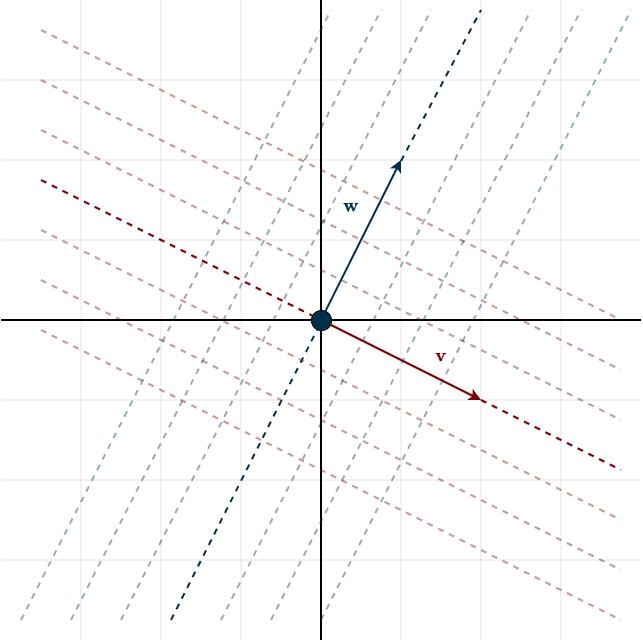

Suppose you have a vector \(\mathbf{v}\). When you scale this vector, you can generate any vector that points in the same direction—this forms a line (as shown by the dotted line in the figure below). However, you can’t produce vectors that lie in a different direction using \(\mathbf{v}\) alone.

Now, introduce another vector \(\mathbf{w}\). Like \(\mathbf{v}\), it has its own direction, and by scaling it, you can create any vector along that direction. The key idea is that vector addition lets us combine these two directions.

By adding scaled versions of \(c\mathbf{v}\) and \(d\mathbf{w}\), we can generate an entire plane of vectors through linear combinations. In fact, this allows us to create every possible vector in two-dimensional space. Look at the following figure:

Here, the dotted lines are spaced \(\frac{1}{4}\) of the vector apart. So, the dotted line above \(\mathbf{v}\) represents any vector that can be written as the linear combination \(\mathbf{x} = c \cdot \mathbf{v} + \frac{1}{4} \mathbf{w} \). The dotted line along \(\mathbf{v}\) is simply offset by some factor of \(\mathbf{w}\). The same is true for the dotted lines with \(\mathbf{w}\), as they are offset by some factor of \(\mathbf{v}\). The image above illustrates the geometry. In theory, with infinite precision, these closely spaced dotted lines fill the entire plane, allowing us to create every possible vector within that space.

Imagine the axes of a 3D printer with a pen attached and a piece of paper beneath it. With only one axis—one direction—it can only draw along a straight line. But once you add a second axis, it can move in two directions and draw anywhere on the paper.

Now, we want to measure how many vectors can be produced as linear combinations of some given vectors.

Span

The set of all linear combinations of a list of vectors \(\mathbf{v}_1, \dots, \mathbf{v}_m\) in \(V\) is called the span of \(\mathbf{v}_1, \dots, \mathbf{v}_m\), denoted by \(\text{span}(\mathbf{v}_1, \dots, \mathbf{v}_m)\). In other words:

\(\text{span}(\mathbf{v}_1, \dots, \mathbf{v}_m) = \{a_1 \cdot \mathbf{v}_1 + \dots + a_m \cdot \mathbf{v}_m : a_1, \dots, a_m \in F \;\}\)

The span of the empty list \(()\) is defined to be \(\{0\}\).

If we look at the figure from above, it’s easy to see that we can create any vector in 2D space using the vectors \(\mathbf{v}\) and \(\mathbf{w}\). That means the span of \(\mathbf{v}\) and \(\mathbf{w}\) is the entire 2D space, \(\mathbb{R}^2\). If you look at the scaling-vector figure, the span of a single vector consists only of multiples of that vector (the dotted line). So if our vector space were \(\mathbb{R}\) (1D), then one vector would be enough to cover every possible vector in that space. If our vector space were \(\mathbb{R}^2\), then two vectors would be enough to create every vector and span the whole space. For \(\mathbb{R}^3\), we’d need three vectors, and so on—you get the idea.

However, there’s one important detail: this only works if the vectors actually point in different directions. Otherwise, we can’t create new directions or reach the full space. In other words, the vectors need to be linearly independent. But what exactly does that mean?

Linear Independence

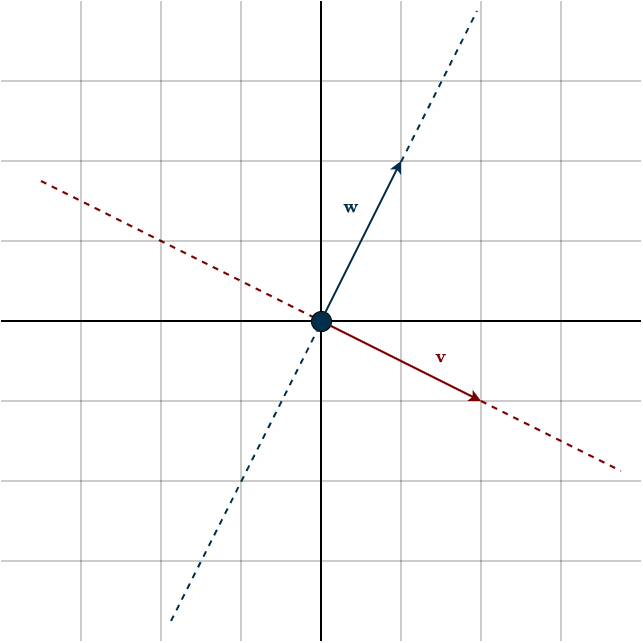

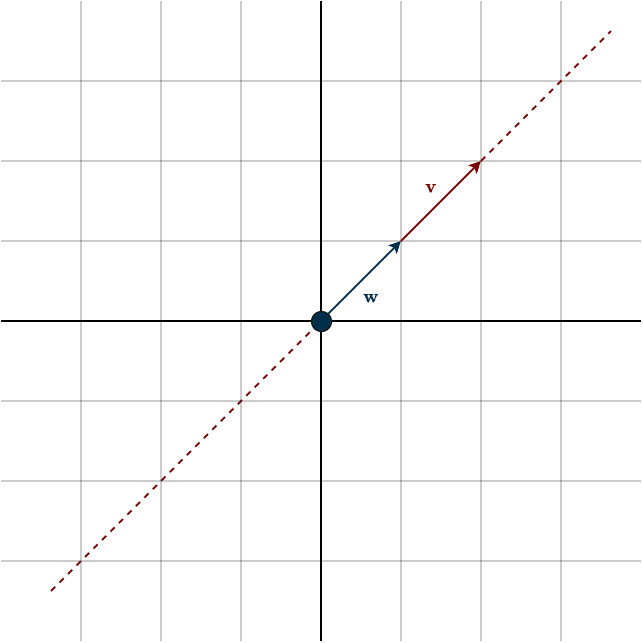

Imagine two vectors pointing in the same direction:

In this case, no matter how we combine the vectors \(\mathbf{v}\) and \(\mathbf{w}\), we remain restricted to the direction they both share. For example, we cannot generate the vector \((-1, -1)\). One vector is simply a scalar multiple of the other: \(\mathbf{w} = \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{v}\) or \(\mathbf{v} = 2\mathbf{w}\). This means we can replace one with a linear combination of the other. Put simply, the second vector does not introduce a new direction or dimension; it’s redundant. It can be replaced without losing any information or dimensionality. We call such vectors linearly dependent. In contrast, vectors that point in different directions, where removing one actually leads to a loss of information or dimension, are called linearly independent.

A single vector is considered linearly independent in \(\mathbb{R}\) if it is non-zero. Two non-zero vectors in \(\mathbb{R^2}\) are linearly independent if they are not scalar multiples of each other—that is, they point in different directions. Three non-zero vectors in \(\mathbb{R^3}\) are linearly independent if the first two are independent and the third is not a linear combination of the previous ones. More generally, a set of non-zero vectors is considered linearly independent if each new vector does not lie in the span of the preceding ones.

(Note that two independent vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) are sufficient to span the entire space. Therefore, any third vector in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) must lie within the span of the first two, meaning that three vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) will always be linearly dependent. We will see this shortly with the definition of the dimension of a vector space.)

The mathematical definition is, as expected, a bit more abstract:

A list \(\mathbf{v}_1, \dots, \mathbf{v}_m\) of vectors in \(V\) is called linearly independent if the only choice of \(a_1, \dots, a_m \in F\) that makes

\(a_1 \cdot \mathbf{v}_1 + \dots + a_m \cdot \mathbf{v}_m = \mathbf{0}\)

is \(a_1 = \dots = a_m = 0\). The empty list \(()\) is also declared to be linearly independent.

To understand where this definition comes from, consider this:

Suppose you have a list of vectors \(\mathbf{v}_1, \dots, \mathbf{v}_m \in V\) and another vector \(\mathbf{v}\) that lies in the span of the previous vectors, so \(\mathbf{v} \in \text{span}(\mathbf{v}_1, \dots, \mathbf{v}_m)\). By the definition of the span, this means there exists a linear combination of the given vectors that equals:

\(\mathbf{v} = a_1 \cdot \mathbf{v}_1, \dots, a_m \cdot \mathbf{v}_m\)

Now, we want to ask if this combination is unique. Suppose, for instance, there is a second linear combination, say:

\(\mathbf{v} = c_1 \cdot \mathbf{v}_1, \dots, c_m \cdot \mathbf{v}_m\)

If we subtract the two equations, we get:

\(0 = (a_1 – c_1) \cdot \mathbf{v}_1, \dots, (a_m – c_m) \cdot \mathbf{v}_m\)

If the only way to express zero as a linear combination of \(\mathbf{v}_1, \dots, \mathbf{v}_m\) is by setting all the scalars to zero, this implies that \(a_k – c_k = 0\) for all \(k\), which means \(a_k = c_k\). Therefore, the linear combination was unique. In other words, if the vectors are linearly independent, then linear combinations of these vectors are unique.

If we look at our example in the figure, we can find multiple combinations that equal zero: \(-2\mathbf{w} + \mathbf{v} = -4\mathbf{w} + 2\mathbf{v} = \dots = 0\). Not unique, not linearly independent.

This definition leads to some important facts to know:

- Every list of vectors in \(V\) containing the \(\mathbf{0}\) vector is linearly dependent. Since you can choose any scalar, multiply it by the zero vector, and zero out every other vector in the combination, the result will be zero.

- If some vectors are removed from a linearly independent list, the remaining list is also linearly independent.

To wrap up this section, we will combine the definitions of span and linear independence.

Basis

A basis of \(V\) is a list of vectors in \(V\) that is linearly independent and spans \(V\).

In a vector space, such as \(\mathbb{R}^2\), we want the basis to uniquely represent every possible vector. If the list of vectors does not span the space, we won’t be able to produce every vector. Similarly, if the vectors are not linearly independent, the linear combination will not be unique. In other words: A list of vectors in a vector space that is small enough to be lineraly independent and big enough so the linear combinations of the list fill up the vector space is called a basis of the vector space.

Looking at the figure at the top of the page, you’ll notice the green and blue vectors. These are basis vectors. We can easily verify that they are linearly independent because they point in different directions (or, equivalently, there is no nonzero linear combination that produces the zero vector). Moreover, they span the entire space, since two linearly independent vectors are sufficient to span \(\mathbb{R}^2\). If we were to add a third vector, it could no longer form a basis, as the set would no longer be independent. This particular basis is special and is known as the standard basis. It is the default basis assumed in linear algebra unless stated otherwise. However, the standard basis is only one choice among infinitely many possible bases.

A vector has different coordinate representations depending on the chosen coordinate system, which is defined by the basis. Essentially, the same vector can be represented by different sets of numbers, depending on the system you’re using. However, it’s still the same vector—just expressed differently. Consider the following analogy:

Imagine there’s a café somewhere in the city. Using the standard map (where north is up and east is to the right), the café might be located at: (2 blocks east, 3 blocks north). So, its coordinates are \((2,3)\). Now, picture using a tilted map where one axis points northeast and the other points northwest. These new axes represent your new basis vectors. On this tilted map, the same café might now have coordinates \((\frac{5}{2}, -\frac{1}{2} )\). The numbers are different, but the café hasn’t moved—only the coordinate system has changed.

Here’s another analogy: Imagine you’re measuring an object with different tools, such as a metric ruler, an inch ruler, or even your thumb. The measurements will vary, but the object itself hasn’t changed.

Bases are important to understand, so make sure you’ve got the concept. Switching between different bases will be important later on, but for now, just assume the standard basis, as we’ve done throughout this section (changing between bases can be a bit confusing at first).

Using the definition of a basis, we can now define the dimension of a vector space.

Dimension

For a given vector space \(\mathbb{R}^n\), any two bases have the same number of vectors—specifically, \(n\). For example, every basis of \(\mathbb{R}^2\) contains exactly two vectors, regardless of which basis we choose. This useful fact allows us to define the dimension of a vector space as follows:

The dimension of a finite-dimensional vector space is the length of any basis of the vector space. It is denoted by \(\text{dim}(V)\).

Finite dimensional vector space means the following:

A vector space is called finite-dimensional if some list of vectors in it spans the space.

If we can construct a list of vectors that spans a vector space, then we say the space is finite-dimensional. The vector space \(\mathbb{R}^n\), which is our primary focus, is finite-dimensional because we can always find a finite list of vectors that spans it. In this course, we will work exclusively with finite-dimensional vector spaces, since our attention is restricted to \(\mathbb{R}^n\). However, it is important to keep in mind that not every concept that holds for finite-dimensional spaces extends to infinite-dimensional ones.

A classic example of an infinite-dimensional vector space is the space of all polynomials. A basis for this space can be written as

\((1, x, ,x^2, x^3, \dots)\)

but this list is infinite—its length is unbounded because the degree of a polynomial can always increase.

These definitions lead to several key facts:

- \(\text{dim}(\mathbb{R}^n) = n\) for every positive integer \(n\). For example, the dimension of \(\mathbb{R}^2 = 2\).

- Any linearly independent list of vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) whose length equals \(\text{dim}(\mathbb{R}^n)\) is a basis of \(\mathbb{R}^n\). For instance, in \(\mathbb{R}^2\), any list of two linearly independent vectors automatically forms a basis.

Summary

- You can form new vectors from a given set of vectors by taking linear combinations of them.

- The collection of all such linear combinations is called the span of those vectors.

- A list of vectors is linearly independent when no vector can be written as a linear combination of the others. Geometrically, they each point in a different direction.

- When a list of vectors both spans the entire vector space and is linearly independent, it is called a basis of that vector space.

- The dimension of a vector space is the length of its basis.