Rank, Null Space, and Invertibility

Which vectors move, where do they end up, and how much information is lost?

Every linear transformation naturally comes with two important sets of vectors: first, the vectors it sends to zero, essentially the ones it “throws away”, and second, the vectors it actually reaches. These two sets form subspaces known as the null space and the column space (or range), respectively. Understanding them will give us significant problem-solving power. Remember that linear transformations are all about moving vectors, but some movements cannot be undone, they are not reversible. We call these transformations, and their corresponding matrices, singular or not invertible. A matrix can fail to be invertible to varying degrees, and we measure this using its rank.

Functions

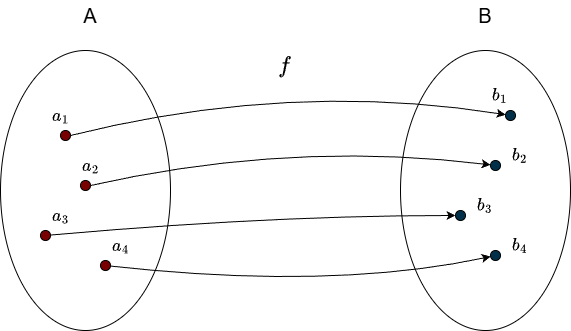

Before introducing the new subspaces, let’s briefly review the basic terminology of functions. Suppose we have two sets \(A\) and \(B\). A function from \(A\) to \(B\) is a rule that assigns to each element of \(A\) exactly one element of \(B\). We denote this by

\(f: A \rightarrow B\)

This idea shouldn’t feel unfamiliar, linear transformations are functions, and we have already discussed them. The set \(A\) from which a function takes its inputs is called the domain, and the set \(B\) that contains all possible outputs is called the codomain. A key requirement is that each input has exactly one output. For example, an element \(a_1 \in A\) cannot be mapped to both \(b_1\) and \(b_2\) at the same time; such ambiguity would violate the definition of a function.

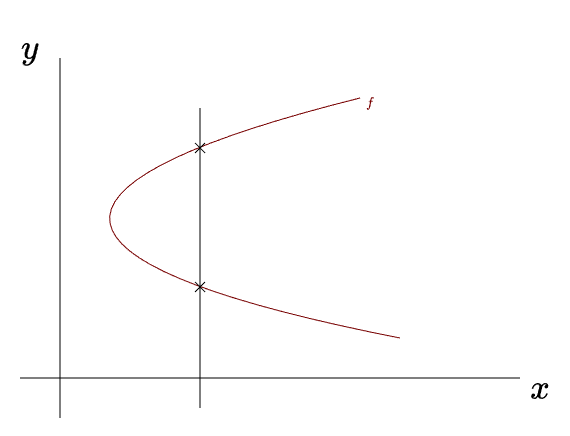

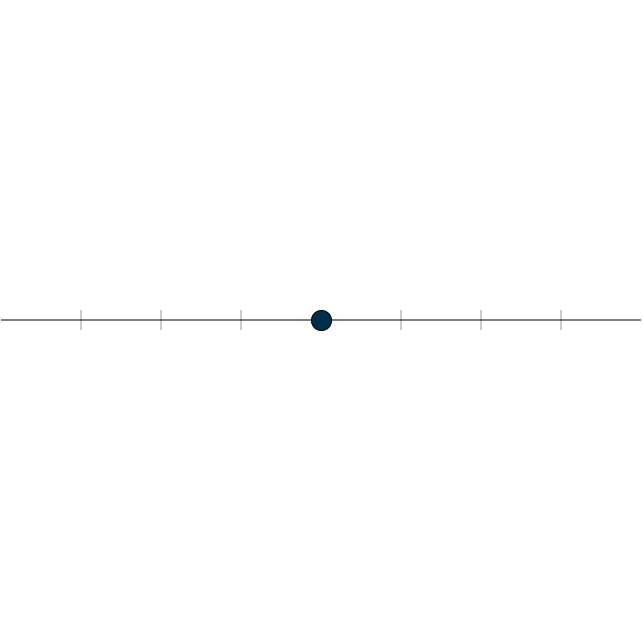

Another way to visualize this is by plotting the relationship between the sets on a graph. Imagine placing the domain on one axis and the codomain on the other. For instance, if both sets are \(\mathbb{R}\), we can represent one along the \(x\)-axis and the other along the \(y\)-axis. A map is a function precisely when it passes the vertical line test: any vertical line should intersect the graph at most once. If a vertical line crosses the graph more than once, the rule assigns multiple outputs to the same input and therefore is not a function. The following curve fails this test:

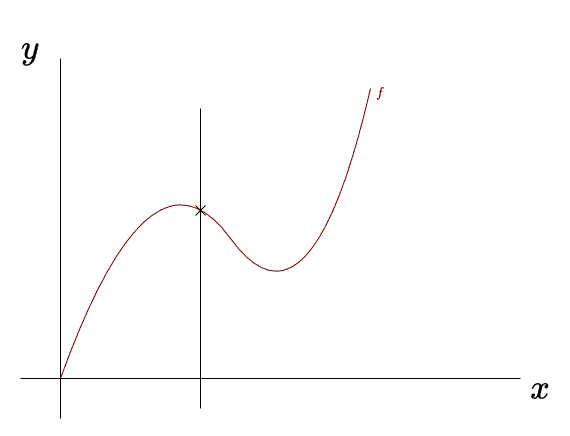

Here is an example of a graph that does pass the vertical line test:

Functions can relate elements of two sets in different ways. Three important properties are injectivity, surjectivity, and bijectivity. Let’s go through them one at a time.

Injectivity

A function is injective (also called one-to-one) if no two different inputs share the same output. In other words, each element of the codomain is mapped to at most once. Formally, a function \(f:A \rightarrow B\) is injective if

\(f(a_1) = f(a_2) \Rightarrow a_1 = a_2\)

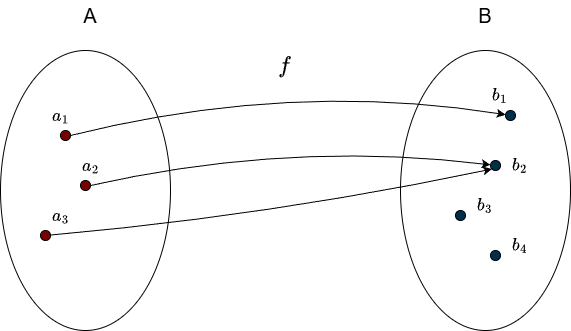

It is perfectly fine for some elements of \(B\) to have no incoming arrows (that is, not be hit by the function at all). What matters is that no element in \(B\) is hit twice. The following example is not injective:

Since \(b_2\) receives arrows from two different elements of \(A\). This still satisfies the definition of a function, but it fails the injectivity condition.

Surjectivity

A function is surjective (also called onto) if every element of the codomain is hit by at least one input from the domain. Formally, a function \(f:A \rightarrow B\) is surjective if

\(f(a) = b \;|\; \forall b \in B, \; \forall a \in A\)

In a surjective function, nothing in the codomain is “left out.” Every element of \(B\) must have at least one incoming arrow.

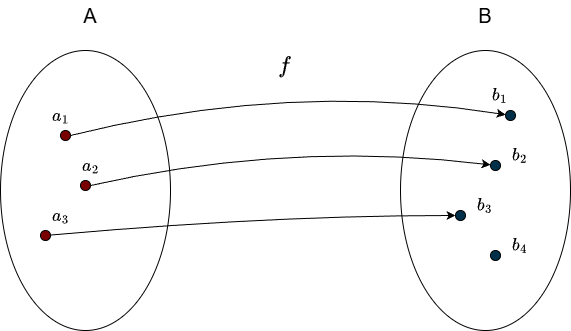

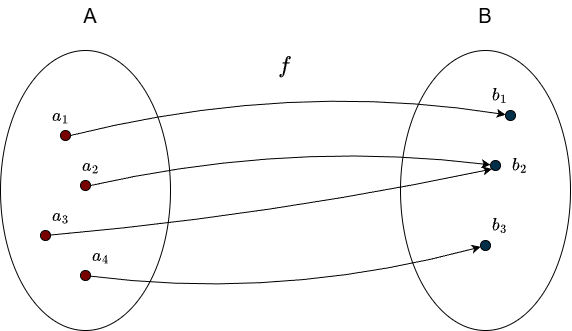

Having multiple incoming arrows is not a problem here, as long as the element is hit at least once. Here is an example of a function that is not surjective:

Since \(b_3\) is not hit, it receives no incoming arrows.

Bijectivity

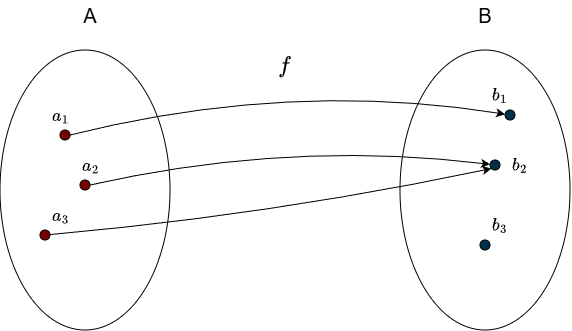

A function is bijective if it is both injective and surjective. This means that each element of \(A\) is mapped to exactly one element of \(B\), and every element of \(B\) is hit by exactly one element of \(A\). In other words, a bijection creates a perfect one-to-one correspondence between the two sets. The figure at the beginning of this section illustrates this idea.

Bijective functions are invertible, they can be “undone.” Because there is a perfect one-to-one correspondence between \(A\) and \(B\), we can simply reverse the arrows. The inverse of a function is denoted by

\(f^{-1}: B \rightarrow A\)

and it reverses the action of \(f\).

This is not possible if the function is only injective or only surjective. If the function is not surjective, some elements of \(B\) have no incoming arrow; reversing the arrows would leave nowhere to go in \(A\). If the function is not injective, some elements of \(B\) have multiple incoming arrows; reversing them would be ambiguous because we wouldn’t know which element of \(A\) to return to. Only bijective functions avoid these problems, which is why they, and only they, have well-defined inverses.

The only thing left to recap is the range of the function.

Range

The range (also called the image of \(f\)) of a function is the set of all actual outputs the function produces. More formally, if

\(f: A \rightarrow B\)

then the range is defined as

\(\text{range}(f) = \{f(a) \; | \; a \in A\} \subseteq B\)

Think of the codomain \(B\) as a city and the function as a radio tower. The range tells you which houses in the city actually receive the signal. In other words, the range is the set of outputs the function truly reaches. For example, consider

\(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}, \hspace{1cm} f(x) = x^2\)

The codomain is all real numbers, but since squaring never produces a negative value, the function never reaches the negative part of \(\mathbb{R}\). Therefore, the range is only the non-negative real numbers.

Surjectivity guarantees that

\(\text{range}(f) = \text{codomain}(f)\)

because it requires that every element of the codomain be hit by at least one input. Now we’re finally ready to tackle the new subspaces.

Null Space

For \(T \in \mathcal{L}(V, W)\), the null space of \(T\), denoted by \(\text{null } T\), is the subset of \(V\) consisting of those vectors that \(T\) maps to \(\mathbf{0}\):

\(\text{null } T = \{ \mathbf{v} \in V: T\mathbf{v} = \mathbf{0}\}\).

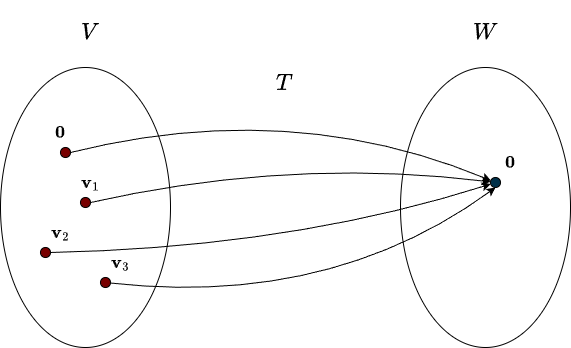

The definition above says that all the vectors that \(T\) maps to zero are gathered into a single set. This set forms a vector space, and we call it the null space, “null” hinting at the fact that it involves the zero vector. It is also sometimes referred to as the kernel. Consider the following figure:

In this example, the set \( \{ \mathbf{0}, \mathbf{v}_1,\mathbf{v}_2, \mathbf{v}_3 \} \) forms the null space of the transformation. Recall that a subset must contain the zero vector to qualify as a subspace. Since every linear transformation satisfies \(T(\mathbf{0}) = \mathbf{0}\), every linear transformation has a null space regardless of its other properties. However, the null space can be larger than the trivial subspace \(\{\mathbf{0}\}\). As soon as it contains a nonzero vector, all scalar multiples of that vector must also lie in the null space, which immediately gives us infinitely many vectors. Note that the null space is a subspace of the input vector space, not the output space. In other words, it’s a subspace of \(V\), it lives in \(\mathbb{R}^n\).

If \(T\) is injective, meaning that every vector in the output space is hit at least once, including the zero vector, then the null space of \(T\) is as small as possible: \(\{\mathbf{0}\}\). Simply put:

injective \(T \Longleftrightarrow\) null space equals \(\{\mathbf{0}\}\)

Notice that this statement works both ways: if the null space is as small as possible, then the transformation is injective. That’s half the story when it comes to checking whether a transformation is invertible. But as soon as there’s even a single nonzero vector in the null space, you can throw invertibility out of your window. Let me make this clearer from the perspective of matrices.

For matrices, the null space is captured by a simple expression:

\(A\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0}\)

Focus on what that expression actually means. Matrix-vector multiplication represents a linear combination of the columns of \(A\). So when we’re looking for the null space, we’re searching for a combination of \(A\)’s columns that adds up to zero. This combination is represented using a vector. Of course, the trivial vector \(\mathbf{0}\) always works, so it’s automatically included.

Example

Consider the following matrix:

\(A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\)

If we multiply the second column by any number while ignoring the first, we get the zero vector. This shows that the vector \((0,1)\) is in the null space:

\(A\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ c \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ c \end{bmatrix} = 1 \cdot 0 + 0 \cdot c = 0\)

with \(c \in \mathbb{R}\). Notice that any multiple of this vector also stays in the null space. In general, if \(A\mathbf{x}=\mathbf{0}\), then

\(A(c\mathbf{x}) = cA\mathbf{x} = c\mathbf{0} = \mathbf{0}\)

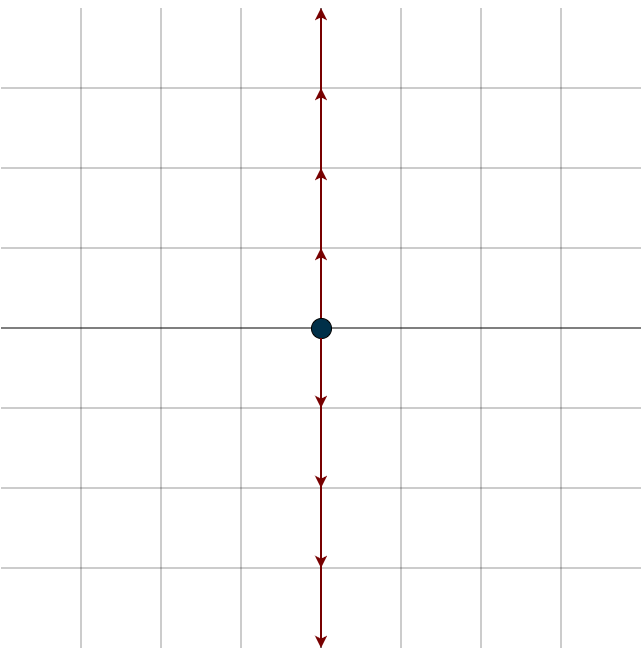

The input space of the matrix is \(\mathbb{R}^2\) and its output space is \(\mathbb{R}\). It only “reads” the first coordinate of any input vector and completely ignores the second. This is exactly the example we saw when we first explored linear transformations: we lose information, we lose a dimension.

You can see that this whole line of vectors gets crushed down to the zero vector by this dimension crusher matrix. Remember, the subspaces of \(\mathbb{R}^n\) include \(\{0\}\), lines, planes, or hyperplanes through the origin. Depending on the matrix, the null space can be any of these subspaces. Geometrically, this means that every vector on that line, plane, or hyperplane is sent to zero after the transformation. It could even be the entire space, take, for example, the following matrix:

\(A = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0\end{bmatrix}\)

This one doesn’t discriminate; it sends every vector to zero. You might think of it like a black hole, sucking in everything around it. Also, the line of vectors that gets mapped to zero doesn’t have to align with the axes. For example, if you take \(A=\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\), the line representing its null space is diagonal, try calculating it yourself.

Finding the basis of the nullspace works the same way for any matrix size. (In short, you put the matrix into reduced row echelon form and identify the free variables).

Column Space / Range

I already mentioned what the range of a function is at the beginning of this chapter. The idea is the same for linear transformations. Basically, the range is the set of all vectors that the linear transformation can actually reach:

For \(T \in \mathcal{L}(V, W)\), the range of \(T\) is the subset of \(W\) consisting of those vectors that are equal to \(T\mathbf{v}\) for some \(\mathbf{v} \in V\):

\(\text{range }T = \{T\mathbf{v} : \mathbf{v} \in V\}\)

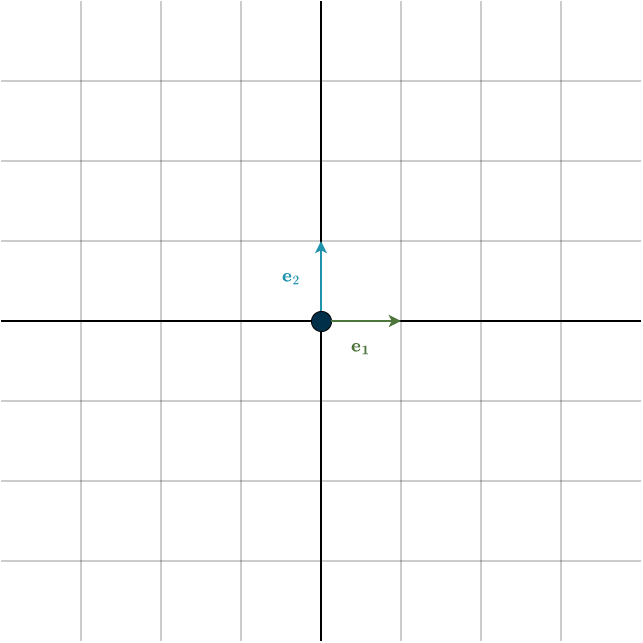

We can express the same idea using matrices (and personally, I prefer this viewpoint). The columns of a matrix are vectors, specifically, they’re the transformed basis vectors. When we multiply a matrix by a vector, we’re forming a linear combination of its columns. To refresh your memory, look at this matrix:

\(A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 5 & 7\end{bmatrix}\)

Multiplying it by a vector \(\mathbf{x}\) gives:

\(A\mathbf{x} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 5 & 7\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 5 \end{bmatrix} \cdot x_1 + \begin{bmatrix} 2 \\ 7 \end{bmatrix} \cdot x_2\)

Remember: the span of a list of vectors is the set of all linear combinations of those vectors. In this case, the vectors are the columns of \(A\). Since these columns are linearly independent, their span is all of \(\mathbb{R}^2\). This span of the columns has a special name: the column space. It is dentoted as \(\text{Col}(A)\), for any given matrix \(A\). The name is fitting, it’s the vector space described by the columns of the matrix. The column space tells you exactly which vectors the matrix can produce. And importantly, it doesn’t always fill the whole space. Consider the matrix:

\(A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 2\end{bmatrix}\)

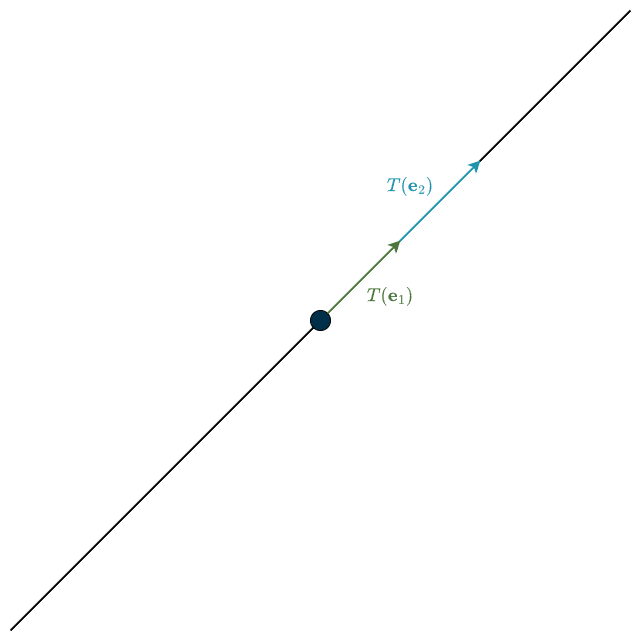

Here the columns are multiples of each other. This means the two different basis vectors are both mapped into the same one-dimensional span of the vector \((1,1)\).

The black line in the right subfigure represents the column space of the matrix. Notice that it’s only one-dimensional and doesn’t cover the entire space. Similarly, in higher-dimensional spaces, the column space can be a line, plane, or hyperplane through the origin.

Since the column space is built from the transformed basis vectors, it should be no surprise that it sits inside \(\mathbb{R}^m\). It is a subspace of the output space. One more helpful fact: if a linear transformation is surjective, then every possible output vector can be produced. In that case, the range, i.e., the column space, is the entire output space.

Fundamental Theorem of Linear Transformations

The next definition is quite important as the name suggets:

Suppose V is finite-dimensional and \(T \in \mathcal{L}(V, W)\). Then \(\text{range } T\) is finite dimensional and

\(\text{dim}(V) = \text{dim(null } T) + \text{dim(range } T)\)

So, once you know the dimension of the column space and the dimension of the input space as a whole, you can calculate the dimension of the null space. The reverse is also true: knowing the null space dimension allows you to find the dimension of the column space. This definition leads to two very useful tricks:

1. Checking whether a transformation has a non-trivial nullspace

Consider an \(m \times n\) matrix. If \(m<n\), the matrix is essentially downscaling: it maps a higher-dimensional space into a lower-dimensional one. The “lost’’ dimensions must go somewhere, they collapse to zero in the nullspace. Therefore, whenever \(m<n\), the linear transformation cannot be injective.

For example, if a transformation maps a 5-dimensional space into a 3-dimensional one, then 2 dimensions are lost in the process. Those 2 dimensions form the nullspace.

If \(m<n\), the matrix is wide, as you can clearly see:

\(\begin{bmatrix}x & x & x &x & x \\ x & x & x &x & x \end{bmatrix}\)

2. Checking at a glance whether the column space can fill the entire output space

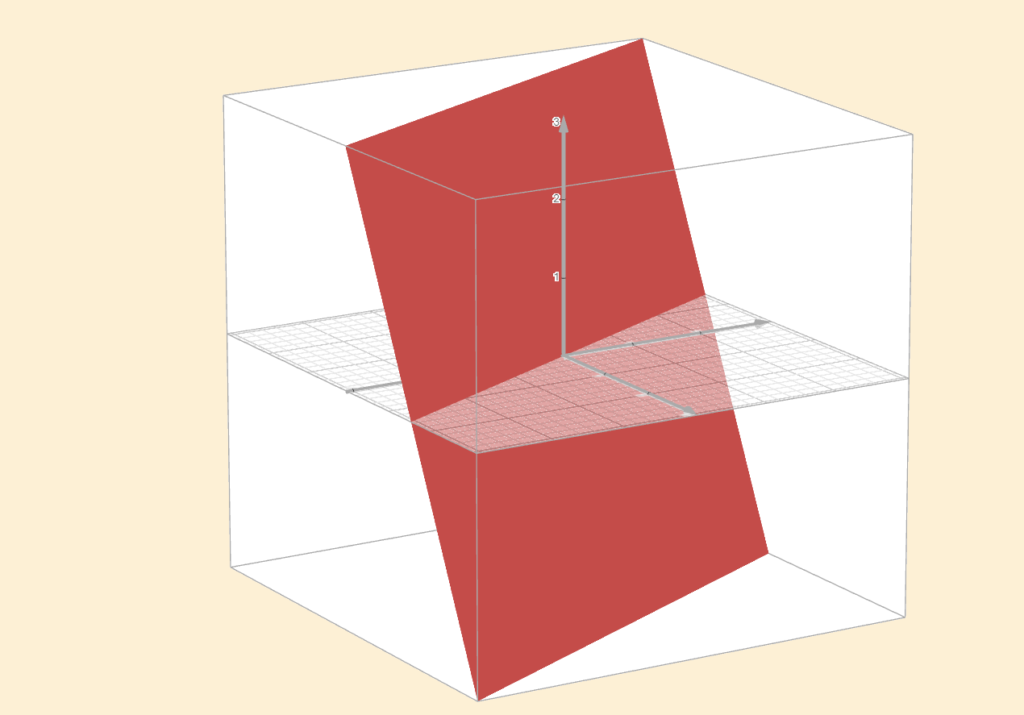

Now consider the opposite situation. If \(m>n\), the matrix is “upscaling’’, trying to map a lower-dimensional space into a higher-dimensional one. The lower-dimensional input cannot possibly fill the entire higher-dimensional output space. This means the transformation cannot be surjective. The column space will not equal the output space.

For instance, mapping a 2-dimensional space into a 3-dimensional one produces a flat plane sitting inside 3D space. No matter how you stretch, rotate, or skew it, that plane can never fill the entire 3D space, just like a sheet of paper cannot touch every point in your room. Vectors above or below the plane simply cannot be reached.

If \(m>n\), the matrix is tall, as you can clearly see:

\(\begin{bmatrix}x & x \\ x & x \\ x & x\\ x & x\\ x & x\end{bmatrix}\)

If a linear transformation loses information, meaning it has a nonzero null space, is it possible to reverse it? Can we simply undo the transformation?

Invertibility

Take another look at the matrix and its associated figure from the earlier discussion of the null space.

\(A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\)

This matrix sends a whole line of vectors to zero.

We cannot reverse this transformation. If we tried, where would the zero vector be mapped back to? We cannot know, because there are infinitely many possibilities. Entire lines of vectors are being compressed into a single vector. For example, every vector of the form

\(\mathbf{v} = (1,c) \; | \; c \in \mathbb{R}\)

gets mapped to the same output. Thinking in terms of functions: there are far too many incoming arrows pointing to the same vector for the mapping to be reversible.

This is exactly why we require injectivity, it ensures that each output vector has at most one arrow pointing to it.

The example above was a dimension crusher, a wide matrix. But we can also have the opposite case: a tall matrix, which maps a lower-dimensional space into a higher-dimensional one, as shown in the figure below. Why is this not invertible either?

Invertibility requires that we can go back from every point in the output space, no exceptions. But with a tall matrix, the column space does not fill the entire output space. That means there are output vectors the transformation never reaches. So if we attempt to reverse it, what happens to those vectors without incoming arrows? They were never produced in the first place, so the reverse mapping has nowhere to send them. This is why we also require surjectivity.

We get invertibility only through a linear transformation that is bijective, both injective and surjective.

We denote the inverse of a matrix \(A\) by \(A^{-1}\). It is defined by the property:

\(AA^{-1} = A^{-1}A = I\)

meaning it perfectly undoes the action of \(A\). The inverse, if it exists, is unique. From this definition, we immediately see that the matrix must be square in order to have a true inverse, since it must be multiplied on both the left and the right. Consequently, \(A^{-1}\) is also square.

It’s generally difficult to say much about the invertibility of a sum like \(A+B\), but the situation is much nicer for a product. The matrix product \(AB\) has an inverse if and only if both \(A\) and \(B\) are individually invertible (and of compatible size). When this happens, the inverse of the product appears in the reverse order:

\((AB)^{-1} = B^{-1}A^{-1}, \hspace{1cm} (ABC)^{-1} = C^{-1}B^{-1}A^{-1}\)

As Gilbert Strang puts it, imagine putting on your socks and then your shoes. To undo that action, you must first take off your shoes and then your socks. The same reversal happens when taking the inverse of a product of matrices.

Rectangular matrices can still have partial inverses: a left inverse or a right inverse. However, as discussed above, they are not fully invertible because they fail either injectivity or surjectivity. Finally, being square is not enough to guarantee invertibility. A square matrix may still fail to be invertible if its columns do not span the entire space as in the example above:

\(A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 2\end{bmatrix}\)

This matrix is square, but notice that the first column is just half of the second. In other words, the columns are linearly dependent, which means their span is only one-dimensional. As a result, this matrix is singular and not invertible.

But this simple example actually illustrates a deeper point. Can we think of “degrees of singularity”? Imagine the output space were ten-dimensional. Depending on the dimension of the matrix’s column space, the matrix could lose more or less information. If the column space is 9-dimensional, the matrix loses only one dimension of information (this lost dimension lives in the nullspace). If the column space is only 5-dimensional, then five dimensions of information are lost, which is clearly worse. Both matrices in these examples are singular / non-invertible, but one clearly discards more information than the other. This raises an important question: can we quantify how much information a matrix loses? How “bad” is a singular matrix?

Rank

We call the dimension of the column space (number of independent column vectors) of a matrix \(A\) the rank of \(A\). For example, if the column space of a matrix is 3-dimensional, then the matrix has rank \(3\). If \(A\) is an \(n \times n\) square matrix and its column space has dimension \(n\) (the maximum possible), then we say that \(A\) has full rank.

So far we have focused on the column space, but there is another important subspace associated with every matrix: the row space of \(A\). It is defined similarly to the column space, except we take the span of the rows rather than the columns. If a matrix has \(n\) columns, then its row space is a subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^n\). We will explore this in more detail later; for now, it’s enough to see that the set of all rows also forms a subspace.

Just as we can talk about column rank, we could in principle talk about row rank, the dimension of the row space. A key theorem in linear algebra says:

column rank = row rank

Because the two ranks are always equal, we simply refer to this common value as the rank of the matrix.

For a rectangular matrix, where \(m \neq n\), the maximum possible rank is \(\text{min}(m,n)\). Since the row and column rank are equal, it is often clearer to specify which dimension we are achieving:

A matrix has full column rank if

\(\text{rank}(A) = \) number of columns.

This means the columns are linearly independent and span the entire output space of the linear transformation.

A matrix has full row rank if

\(\text{rank}(A) = \) number of rows.

Here the rows are linearly independent and span the entire input space.

You can have full column rank or full row rank in rectangular matrices, but never both at the same time unless the matrix is square. A square matrix has both full column rank and full row rank, so we just say the matrix is full rank.

Let’s look at some examples:

1. A full-rank matrix

\(\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 7 \\ 3 & 4 \end{bmatrix}\)

The columns are linearly independent, so the column space is 2-dimensional. Hence, the matrix has rank \(2\). Since it is a \(2 \times 2\) matrix, this means it has full rank.

2. A square matrix of rank 1

\(\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 2 \end{bmatrix}\)

One column is a multiple of the other, so the column space is 1-dimensional. The rows show the same dependency, showing that the row and column rank match.

3. A tall matrix with full column rank

\(\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 4 & 7 \\ 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}\)

Its two columns are linearly independent, so the column space is 2-dimensional. Thus, the matrix has full column rank.

4. A wide matrix with full row rank

\(\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 4 \\ 7 & 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}\)

The rows are linearly independent, so the row space is 2-dimensional. Hence, the matrix has full row rank.

The rank tells us how many dimensions we “keep” after applying the linear transformation. The higher the rank, the fewer dimensions we lose; the lower the rank, the more information collapses. A square matrix is invertible if and only if we lose no dimensions at all, which means it must have full rank.

With rectangular matrices we cannot talk about a true inverse, but we can talk about partial inverses. If you want to apply a left inverse, the matrix needs to have full column rank. If you want to apply a right inverse, it needs full row rank. This simply reflects the idea that, depending on which side you want to invert from, the transformation must preserve all dimensions on that side.

So, to keep in mind: a square matrix is invertible exactly when it has full rank. Full rank means the column space spans the entire output space, or in other words \(\text{rank}(A)=n\). This happens only when the columns are linearly independent. This relationship between invertibility, linear independence, and rank is important, so make sure you understand it well.

I’ll repeat this once more because it’s important: if a matrix has full column rank, its nullspace contains only the zero vector, which means the associated linear transformation is injective. This fact will become especially important later on when we work with least squares.

The rank of a product of matrices is slightly more interesting. Recall that matrix multiplication can be viewed from two complementary perspectives. Given a product \(AB\), the matrix \(A\) multiplies \(B\) on the left, while \(B\) multiplies \(A\) on the right.

When multiplying on the right, the rows of \(AB\) are linear combinations of the rows of \(B\). This means the row space of \(AB\) is contained in the row space of \(B\), and therefore

\(\text{rank}(AB) \leq \text{rank}(B)\)

Similarly, when multiplying on the left, the columns of \(AB\) are linear combinations of the columns of \(A\). Hence, the column space of \(AB\) is contained in the column space of \(A\), which implies

\(\text{rank}(AB) \leq \text{rank}(A)\)

Putting these observations together, we conclude that

\(\text{rank}(AB) \leq \min(\text{rank}(A), \text{rank}(B))\)

Finally, if a matrix is multiplied by an invertible matrix (on either side), its rank does not change. Invertible transformations preserve all linear information, so no dimensions of the row space or column space are lost.

Summary

- Every linear transformation \(T\) comes with two subspaces: the nullspace and the column space.

- Every vector that \(T\) sends to zero ends up in the nullspace.

- Every vector that \(T\) can actually reach lies in the column space (range).

- These satisfy the relationship: \(\text{dim } V = \text{dim(null } T) + \text{dim(range } T)\).

- If \(m<n\) (a wide matrix), the nullspace will be larger than just \(\{0\}\).

- If \(m>n\) (a tall matrix), the column space will not span the whole output space.

- Some transformations cannot be reversed and are therefore not invertible, either because they crush dimensions and lose information, or because they do not cover the whole space.

- Only square matrices can have a true inverse, provided their columns are linearly independent, meaning the column space spans the entire space.

- Rectangular matrices can have partial inverses, in the form of a left inverse or a right inverse.

- The rank of a matrix tells us how much information is lost. It is the dimension of the column space or the row space, and the row rank equals the column rank.

- A matrix is invertible if and only if it has full rank, which means no information is lost.