Subspaces

Can a small group of vectors inside a vector space form their own vector space?

A subset of a vector space \(V\) can itself form a vector space, called a subspace, provided it satisfies certain conditions. Subspaces can be combined to form larger spaces in two ways: one in which their overlap is irrelevant, and another in which the overlap plays a role.

Subset

Remember that a set is simply a collection of objects, where the order of elements does not matter and duplicates are ignored. Sets can contain other sets as well, and any collection of elements taken from a set is called a subset. For example, consider the set:

\(A = \{1,2,3\}\)

Some subsets of \(A\) include:

\(B = \{\}, \{1\}, \{1,2\}, \{2,3\}, \dots\)

In general, a subset is formed by selecting some (or all) elements of the original set. We denote that \(B\) is a subset of \(A\) using the symbol \(B \subseteq A\).

A few important points about subsets:

- A set is always a subset of itself. So for any set \(A\), the expression \(A \subseteq A\) is valid.

- If a subset \(B\) contains fewer elements than the original set \(A\), it is called a proper subset, and we denote it with the symbol: \(B \subset A\). For instance, the set \(B = \{1,2\}\) is a proper subset of \(A\), because it does not contain all the elements of \(A\) (specifically, element \(3\) is missing).

- The empty set \(\{\}\) is considered a subset of every set, including itself.

Subspace

Remember that a vector space \(V\) is a set whose elements, called vectors, can be added together and multiplied by scalars in a way that satisfies certain rules. In our case, these vectors are lists of numbers.

Now, you might wonder: can a subset of a vector space itself form a vector space? In other words, can a vector space contain smaller vector spaces within it? The answer is yes, and these special subsets are called subspaces. Here is the formal definition:

A subset \(U\) of the vector space \(V\) is called a subspace of \(V\) if \(U\) is also a vector space with the same additive identity, addition, and scalar multiplication as on \(V\). In other words, \(U\) needs to satisfy the following three conditions:

Additive Identity:

\(\hspace{1cm}\mathbf{0} \in U\).

Closed under Addition:

\(\hspace{1cm}u + w \in U\) for all \(u, w \in U\).

Closed under Scalar Multiplication

\(\hspace{1cm}a \cdot u \in U\) for all \(a \in F, u \in U\).

To gain a clearer understanding, consider the following examples:

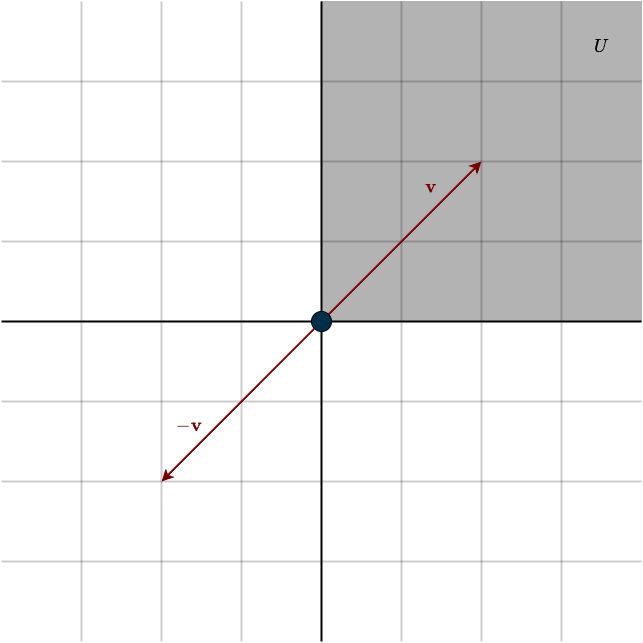

Example 1: Upper Right Quadrant of \(\mathbb{R}^2\)

This refers to the set of vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) where all components are positive. Let’s check if this set is a subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^2\) by examining the necessary conditions:

- Zero Vector: The zero vector would be included in this set (since we consider zero to be “positive” here), so it satisfies this condition.

- Closed under Addition: The set is closed under addition. If you add two vectors, both with positive components, the result will also have all positive components, so this condition holds.

- Closed under Scalar Multiplication: This condition fails. Scalar multiplication is not closed because a scalar can be any real number, including negative numbers. If you multiply a vector with a negative scalar, its components will become negative, violating the condition.

Therefore, this set is not a subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^2\).

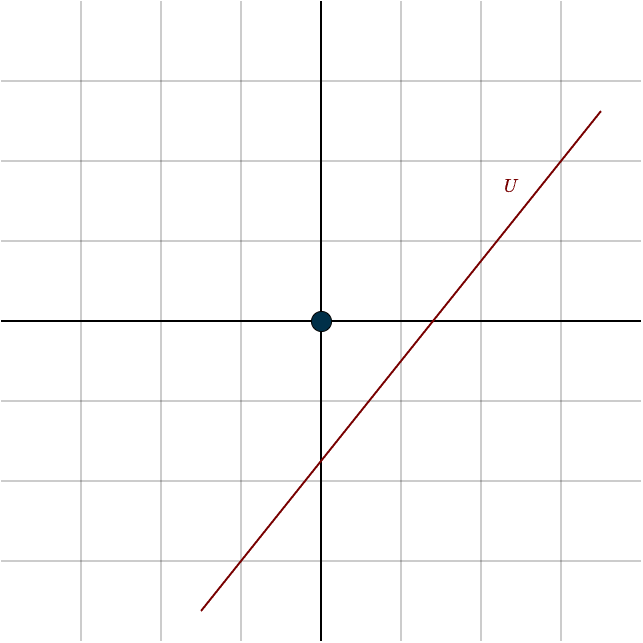

Example 2: A Line in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) Not Crossing the Origin

- Zero Vector: This example fails immediately because the zero vector is not included in the set. Since the zero vector is essential for any subspace, this set cannot be a subspace.

Thus, this set is not a subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^2\).

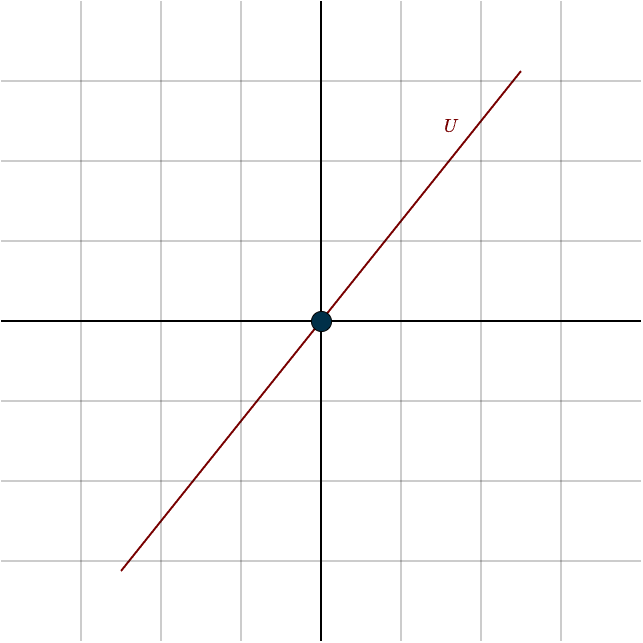

Example 3: A Line in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) Through the Origin

- Zero Vector: The zero vector is explicitly included in this set, as it passes through the origin.

- Closed under Addition: The set is closed under addition. If you add two vectors that lie on the same line, the result is simply a scaled version of the original vector, which also lies on the line.

- Closed under Scalar Multiplication: The set is closed under scalar multiplication. Any scalar multiple of a vector on this line still lies on the line, preserving its span.

Therefore, this set is a subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^2\). (The choice of the line was arbitrary; any line in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) that passes through the origin is a subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^2\))

The subset containing only the zero vector, \(\{0\}\), is also a subspace. It satisfies all the conditions:

- it includes the zero vector.

- is closed under addition (since \(0 + 0 = 0\)).

- is closed under scalar multiplication (since multiplying \(0\) by any scalar results in \(0\)).

It is the smallest subspace of any vector space.

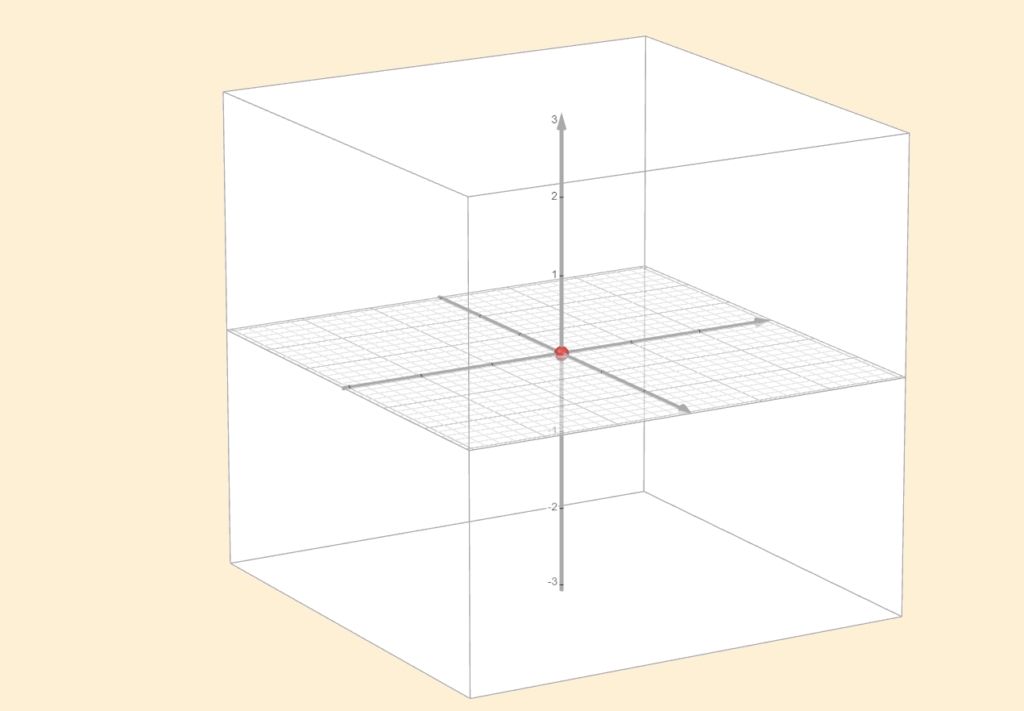

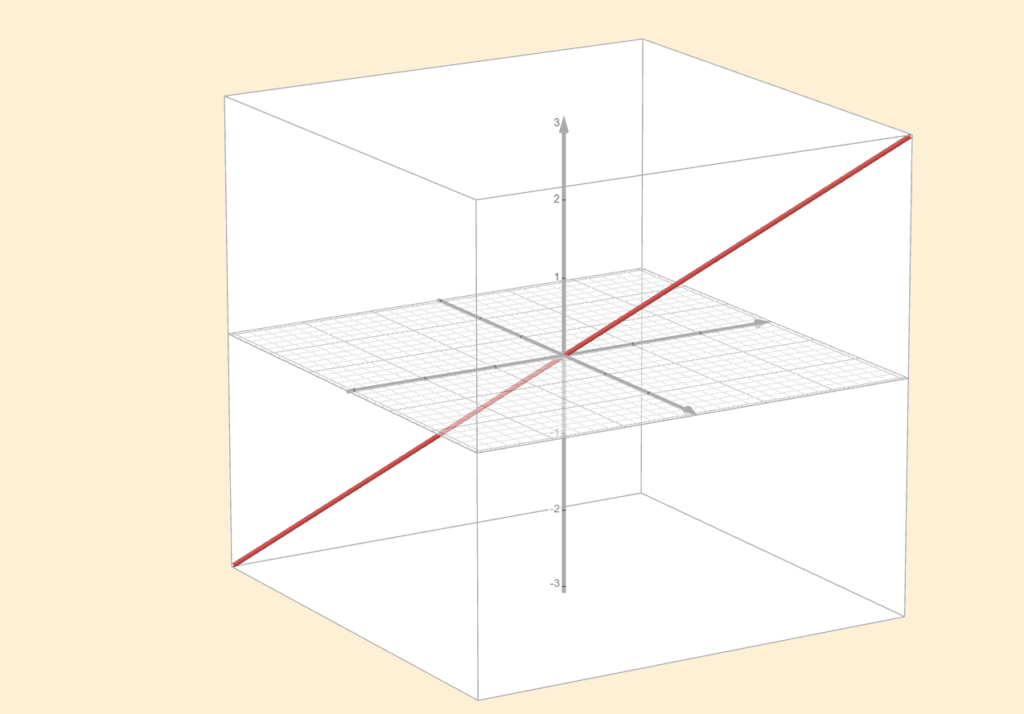

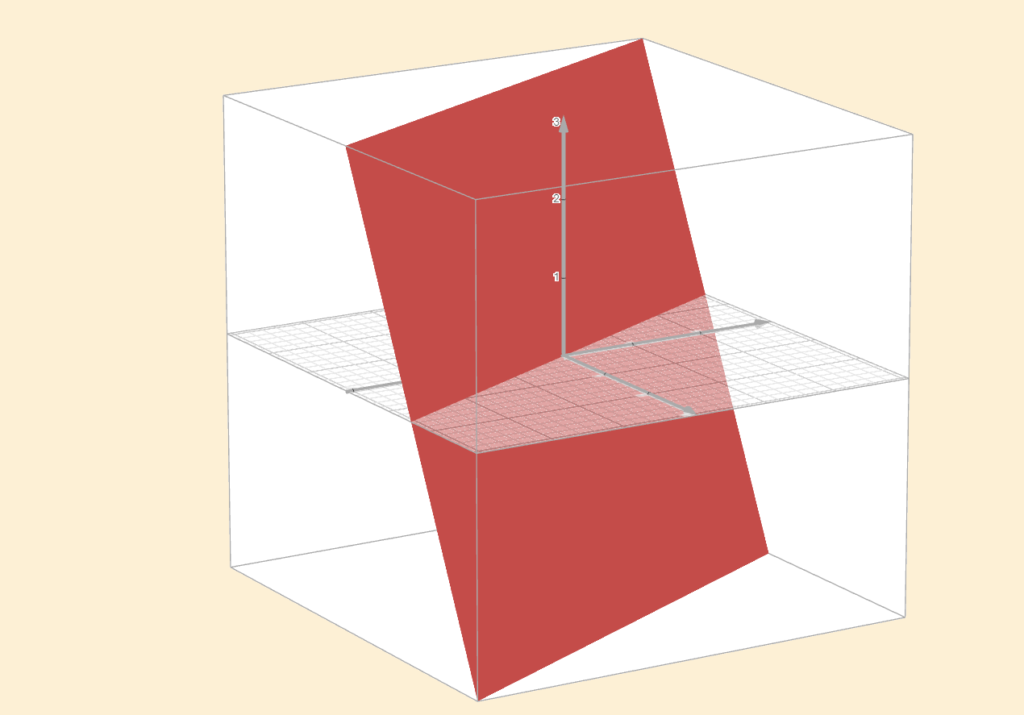

In this course, we focus primarily on \(\mathbb{R}^n\), where the subspaces are straightforward to identify. For instance, the subspaces of \(\mathbb{R}^3\) are precisely:

1. \(\{0\}\) (the zero vector alone)

2. All lines in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) passing through the origin

3. All planes in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) passing through the origin

4. \(\mathbb{R}^3\) itself

Remember, a set can always be a subset of itself, which is why \(\mathbb{R}^3\) is also a subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^3\). For \(\mathbb{R}^2\) the subspaces are precisely: \(\{0\}\), All lines in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) passing through the origin and \(\mathbb{R}^2\) itself.

You might be tempted to think that a plane embedded in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) is \(\mathbb{R}^2\), but this is not correct. The space \(\mathbb{R}^2\) consists of two-dimensional vectors with two coordinates, whereas a plane in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) is made up of three-dimensional vectors, each with three coordinates. Although the two can look similar, they are fundamentally different, so it is important to keep this distinction in mind.

At this point, one might ask: if a vector space has multiple subspaces, how do these subspaces interact with one another?

Sum of Subspaces

Suppose \(U_1, \dots, U_m\) are subspaces of \(V\). The sum of \(U_1, \dots, U_m\), denoted by \(U_1 + \dots + U_m\), is the set of all possible sums of elements of \(U_1, \dots, U_m\). More precisely:

\(U_1, \dots, U_m = \{\mathbf{v}_1 + \dots + \mathbf{v}_m : \mathbf{v}_1 \in U_1, \dots, \mathbf{v}_m \in U_m\}\)

This definition leads to a neat fact:

The sum of subspaces is itself a subspace; in fact, it is the smallest subspace that contains all of the summands (the vector spaces being added). Moreover, the span of the given vectors, each corresponding to its own subspace, is exactly this smallest containing subspace.

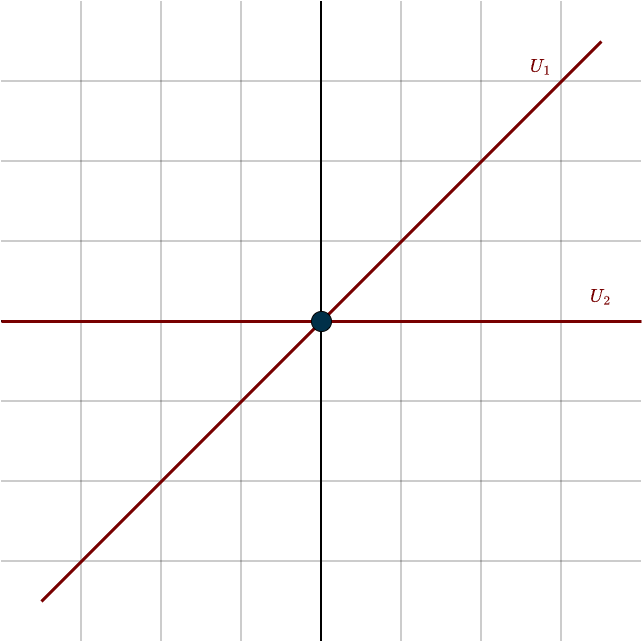

To clarify the concept of the sum of subspaces, consider the vector space \(\mathbb{R}^2\) and two lines passing through the origin. These lines will represent our two subspaces, which we will call \(U_1\) and \(U_2\). Each subspace can be represented as the span of a vector:

Let \(\mathbf{v}_1 = (1,1)\), so that \(U_1=\text{span}(\mathbf{v}_1)\)

Let \(\mathbf{v}_2 = (1,0)\), so that \(U_2=\text{span}(\mathbf{v}_2)\)

Mathematically, these subspaces can be written as:

\(U_1 = \{(s,s) \in \mathbb{R}^2: s \in \mathbb{R}\}, \hspace{1cm} U_2 = \{(t, 0) \in \mathbb{R}^2: t \in \mathbb{R}\}\)

\(U_1\) consists of all vectors pointing in the 45° direction, where the coordinates are equal. \(U_2\) consists of all vectors along the first axis, where the second coordinate is zero. The sum of these two subspaces is defined as:

\(U = U_1 + U_2 = \{(s + t, s) \in \mathbb{R}^2 : s,t \in \mathbb{R}\}\)

Here, the first component \(s + t\) can take any real value because \(s\) and \(t\) can vary independently, and the second component \(s\) can also be any real number. Therefore, the sum \(U\) covers the entire plane \(\mathbb{R}^2\). Notice that the individual subspaces alone are not enough to cover the plane but by adding vectors from both subspaces, we can reach any point in \(\mathbb{R}^2\).

This is exactly what we have seen with linear combinations:

\(s \cdot \mathbf{v}_1 + t \cdot \mathbf{v}_2 = s \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 1\\ 1\\ \end{bmatrix} + t \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 1\\ 0\\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} s\\ s\\ \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} t\\ 0\\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} s + t\\ s\\ \end{bmatrix}\)

Remember that the span of a list of vectors is the set of all linear combinations of those vectors. It always forms a subspace, specifically, the smallest subspace containing all the vectors. Each individual vector also has a span, which is a subspace on its own. If you take two vectors and consider the span of each vector separately, you get two subspaces. The sum of these two subspaces is exactly the same as the span of the two vectors together: all possible linear combinations of vectors from the two subspaces:

\(\text{span}(\mathbf{v}_1) + \text{span}(\mathbf{v}_2) = \text{span}(\mathbf{v}_1, \mathbf{v}_2)\)

Notice that vector spaces or subspaces do not need to be distinct; in other words, they can overlap. Subspaces can share vectors, and this overlap is perfectly valid in the definition of the sum of subspaces.

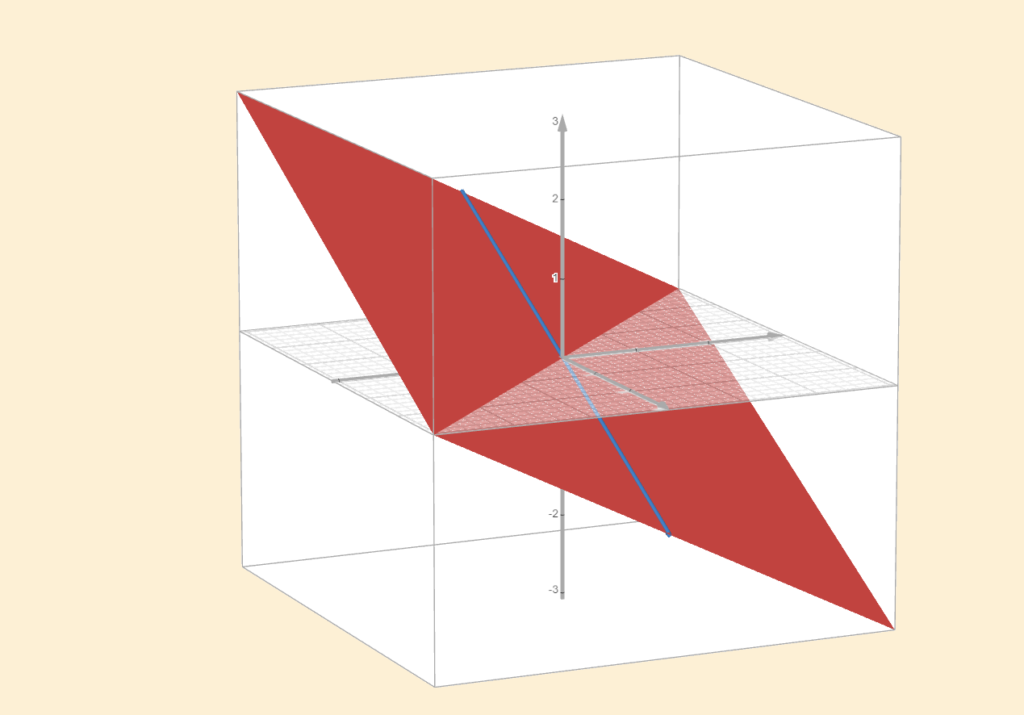

For example, in \(\mathbb{R}^3\), possible subspaces include planes and lines that pass through the origin. If a line lies entirely within a plane, the sum of the two subspaces will simply be the plane itself. This is because the line does not contribute any new directions beyond those already covered by the plane, it’s redundant. The line can be described as a linear combination of the vectors in the plane.

To sum up, the sum of subspaces allows for overlap. Subspaces can share vectors, and their sum is simply the span of all the vectors in both subspaces. However, this is different from the definition of a direct sum.

Direct Sum

Suppose \(U_1, \dots, U_m\) are subspaces of \(V\).

The sum \(U_1 + \dots + U_m\) is called a direct sum if each element of \(U_1 + \dots + U_m\) can be written in only one way as a sum \(\mathbf{v}_1, \dots, \mathbf{v}_m\), where each \(\mathbf{v}_k \in U_k\).

If \(U_1 + \dots + U_m\) is a direct sum, then \(U_1 \oplus \dots \oplus U_m\) denotes \(U_1 + \dots + U_m\), with the \(\oplus\) notation serving as an indication that this is a direct sum.

If we have two subspaces as input, then essentially, the direct sum of vector spaces is a way to combine them without any overlap. Formally, the two subspaces only share the zero vector, no other vectors are common, which ensures that every vector in the combined space can be written in a unique way as a sum of vectors from each subspace:

\(U_1 \cap U_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}\)

The symbol \(\cap\) represents the intersection of two sets. It tells us what elements the sets have in common.

For example, if we take \(U_1\) and \(U_2\) from the example above, they only intersect at the zero vector, their sum is a direct sum. There is no overlap, and each vector in the space can be decomposed in exactly one way.

When adding three or more subspaces in a direct sum, it’s not enough to check only pairwise intersections. Even if every pair of subspaces intersects only in the zero vector, the entire collection might still overlap in a more complicated way.

To guarantee a direct sum in this case, you need two things:

- The sum of all the subspaces equals the whole space \(V\).

- Each subspace intersects the sum of all the others only at \(0\):

\(U_i \cap \Big( \sum_{j \neq i} U_j\Big) = \{0\}\)

The core idea is the same: no overlap. If there is any non-zero overlap, then a vector in the combined space could be written in more than one way, creating ambiguity.

A direct sum avoids this by ensuring every vector can be decomposed in exactly one way, with one component coming from each subspace. The earlier example of a line lying inside a plane illustrates the problem: any vector on that line can be generated by vectors from the line, but it can also be generated entirely by vectors from the plane, since the line is contained within it. Because the same vector can be produced in two different ways, the decomposition is not unique, and therefore the sum is not a direct sum.

Later, we’ll introduce something called an inner product, which essentially upgrades our vector space by letting us measure distances and angles. But notice that the definition of a direct sum does not require subspaces to be perpendicular to each other. It only requires uniqueness in the decomposition. Even if \(U_1\) and \(U_2\) are not at right angles, as long as they only share the zero vector, their sum is a direct sum.

The definition of the direct sum also gives the following important fact:

Suppose \(V\) is finite-dimensional and \(U\) is a subspace of \(V\). Then there is a subspace \(W\) of \(V\) such that \(V\) = \(U \oplus W\).

Let’s consider any subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^n\). There will always be another subspace that “completes” the first one, filling in the rest of the space that was not covered by the first subspace.

For example, suppose our vector space is \(\mathbb{R}^3\), and our subspace is a line through the origin. This subspace is 1-dimensional, since its basis consists of a single vector, and we can generate any vector along that line by scaling this basis vector. However, \(\mathbb{R}^3\) is 3-dimensional, so there is a 2-dimensional subspace missing to complete the entire space.

In this case, we can find a 2-dimensional plane (in fact, there are infinitely many such planes) passing through the origin, and the direct sum of the line and the plane will span all of \(\mathbb{R}^3\). This works because the definition of a direct sum requires that the subspaces do not overlap except at the zero vector. In this case, the line and the plane only intersect at the origin, so their direct sum gives us the entire 3-dimensional space, \(\mathbb{R}^3\).

You can often tell right away whether two subspaces will overlap just by looking at their dimensions. For instance, take \(\mathbb{R}^3\) and consider a plane through the origin, which is a 2-dimensional subspace. If you add another plane like this, there’s no way they can avoid overlapping. Since \(\mathbb{R}^3\) is only three-dimensional, two 2-dimensional subspaces simply don’t have enough “room” to be disjoint except at the zero vector. To have two 2-dimensional subspaces with no overlap, you’d need a space of dimension four or higher.

It’s important to keep this in mind, as it will be useful later when we discuss the four fundamental subspaces of a linear transformation.

Dimension of a Subspace

If \(V\) is finite-dimensional and \(U\) is a subspace of \(V\), then \(\text{dim}(U) \leq \text{dim}(V)\).

If \(\text{dim}(U) = \text{dim}(V)\), then \(U\) = \(V\).

For example, consider the vector space \(\mathbb{R}^3\). A possible subspace within this space could be a line passing through the origin. Here, the basis has length \(1\). To define this line, only a single vector is needed, as scaling this vector generates all other vectors along that direction. Consequently, the dimension of this subspace is \(1\), which is smaller than the dimension of \(\mathbb{R}^3\), which is \(3\).

Summary

- Taking some part (or the whole) of a set is called a subset.

- Certain subsets of a vector space \(V\) can themselves form a vector space if they satisfy certain rules. These are then referred to as subspaces of \(V\).

- Subspaces can be added together to create larger spaces. The standard sum does not care about overlap.

- The direct sum is a stricter type of sum that requires uniqueness in decomposition; subspaces cannot overlap, except at the zero vector.