Invertibility and Rank

Linear transformations are all about moving vectors, but some movements cannot be undone, they are not reversible. We call these transformations, and their corresponding matrices, singular or not invertible. A matrix can fail to be invertible to varying degrees, and we measure this using its rank. Let’s start with invertibility.

Invertibility

Consider the matrix from the previous chapter:

\(A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\)

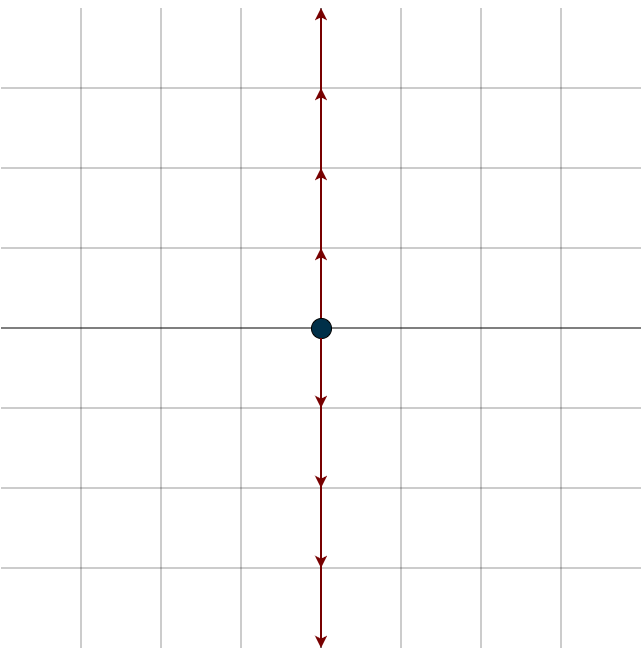

This matrix sends a whole line of vectors to zero:

We cannot reverse this transformation. If we tried, where would the zero vector be mapped back to? We cannot know, because there are infinitely many possibilities. Entire lines of vectors are being compressed into a single vector. For example, every vector of the form

\(\mathbf{v} = (1,c) \; | \; c \in \mathbb{R}\)

gets mapped to the same output. Thinking in terms of functions: there are far too many incoming arrows pointing to the same vector for the mapping to be reversible.

This is exactly why we require injectivity, it ensures that each output vector has at most one arrow pointing to it.

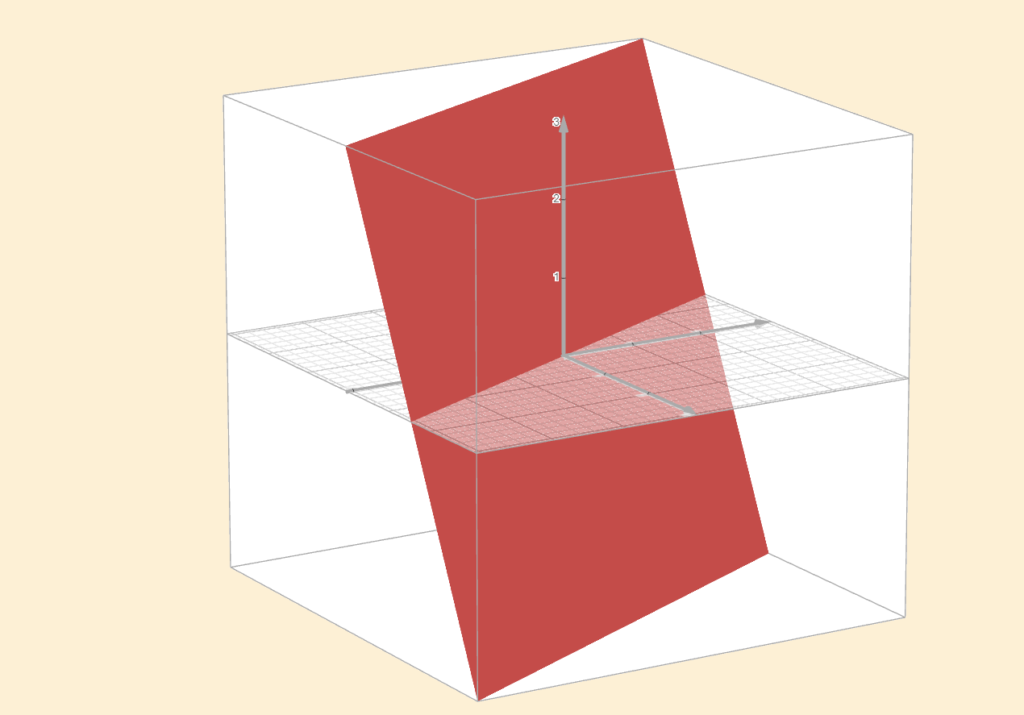

The example above was a dimension crusher, a wide matrix. But we can also have the opposite case: a tall matrix, which maps a lower-dimensional space into a higher-dimensional one, as shown in the figure below. Why is this not invertible either?

Invertibility requires that we can go back from every point in the output space, no exceptions. But with a tall matrix, the column space does not fill the entire output space. That means there are output vectors the transformation never reaches. So if we attempt to reverse it, what happens to those vectors without incoming arrows? They were never produced in the first place, so the reverse mapping has nowhere to send them. This is why we also require surjectivity.

We get invertibility only through a linear transformation that is bijective, both injective and surjective.

We denote the inverse of a matrix \(A\) by \(A^{-1}\). It is defined by the property:

\(AA^{-1} = A^{-1}A = I\)

meaning it perfectly undoes the action of \(A\). The inverse, if it exists, is unique. From this definition, we immediately see that the matrix must be square in order to have a true inverse, since it must be multiplied on both the left and the right. Consequently, \(A^{-1}\) is also square.

It’s generally difficult to say much about the invertibility of a sum like \(A+B\), but the situation is much nicer for a product. The matrix product \(AB\) has an inverse if and only if both \(A\) and \(B\) are individually invertible (and of compatible size). When this happens, the inverse of the product appears in the reverse order:

\((AB)^{-1} = B^{-1}A^{-1}, \hspace{1cm} (ABC)^{-1} = C^{-1}B^{-1}A^{-1}\)

As Gilbert Strang puts it, imagine putting on your socks and then your shoes. To undo that action, you must first take off your shoes and then your socks. The same reversal happens when taking the inverse of a product of matrices.

Rectangular matrices can still have partial inverses: a left inverse or a right inverse. However, as discussed above, they are not fully invertible because they fail either injectivity or surjectivity. Finally, being square is not enough to guarantee invertibility. A square matrix may still fail to be invertible if its columns do not span the entire space. Consider the following matrix:

\(A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 2\end{bmatrix}\)

This matrix is square, but notice that the first column is just half of the second. In other words, the columns are linearly dependent, which means their span is only one-dimensional. As a result, this matrix is singular and not invertible.

But this simple example actually illustrates a deeper point. Can we think of “degrees of singularity”? Imagine the output space were ten-dimensional. Depending on the dimension of the matrix’s column space, the matrix could lose more or less information. If the column space is 9-dimensional, the matrix loses only one dimension of information (this lost dimension lives in the nullspace). If the column space is only 5-dimensional, then five dimensions of information are lost, which is clearly worse. Both matrices in these examples are singular / non-invertible, but one clearly discards more information than the other. This raises an important question: can we quantify how much information a matrix loses? How “bad” is a singular matrix?

Rank

We call the dimension of the column space (number of independent column vectors) of a matrix \(A\) the rank of \(A\). For example, if the column space of a matrix is 3-dimensional, then the matrix has rank \(3\). If \(A\) is an \(n \times n\) square matrix and its column space has dimension \(n\) (the maximum possible), then we say that \(A\) has full rank.

So far we have focused on the column space, but there is another important subspace associated with every matrix: the row space of \(A\). It is defined similarly to the column space, except we take the span of the rows rather than the columns. If a matrix has \(n\) columns, then its row space is a subspace of \(\mathbb{R}^n\). We will explore this in more detail later; for now, it’s enough to see that the set of all rows also forms a subspace.

Just as we can talk about column rank, we could in principle talk about row rank, the dimension of the row space. A key theorem in linear algebra says:

column rank = row rank

Because the two ranks are always equal, we simply refer to this common value as the rank of the matrix.

For a rectangular matrix, where \(m \neq n\), the maximum possible rank is \(\text{min}(m,n)\). Since the row and column rank are equal, it is often clearer to specify which dimension we are achieving:

A matrix has full column rank if

\(\text{rank}(A) = \) number of columns.

This means the columns are linearly independent and span the entire output space of the linear transformation.

A matrix has full row rank if

\(\text{rank}(A) = \) number of rows.

Here the rows are linearly independent and span the entire input space.

You can have full column rank or full row rank in rectangular matrices, but never both at the same time unless the matrix is square. A square matrix has both full column rank and full row rank, so we just say the matrix is full rank.

Let’s look at some examples:

1. A full-rank matrix

\(\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 7 \\ 3 & 4 \end{bmatrix}\)

The columns are linearly independent, so the column space is 2-dimensional. Hence, the matrix has rank \(2\). Since it is a \(2 \times 2\) matrix, this means it has full rank.

2. A square matrix of rank 1

\(\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 2 \end{bmatrix}\)

One column is a multiple of the other, so the column space is 1-dimensional. The rows show the same dependency, showing that the row and column rank match.

3. A tall matrix with full column rank

\(\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 4 & 7 \\ 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}\)

Its two columns are linearly independent, so the column space is 2-dimensional. Thus, the matrix has full column rank.

4. A wide matrix with full row rank

\(\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 4 \\ 7 & 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}\)

The rows are linearly independent, so the row space is 2-dimensional. Hence, the matrix has full row rank.

The rank tells us how many dimensions we “keep” after applying the linear transformation. The higher the rank, the fewer dimensions we lose; the lower the rank, the more information collapses. A square matrix is invertible if and only if we lose no dimensions at all, which means it must have full rank.

With rectangular matrices we cannot talk about a true inverse, but we can talk about partial inverses. If you want to apply a left inverse, the matrix needs to have full column rank. If you want to apply a right inverse, it needs full row rank. This simply reflects the idea that, depending on which side you want to invert from, the transformation must preserve all dimensions on that side.

So, to keep in mind: a square matrix is invertible exactly when it has full rank. Full rank means the column space spans the entire output space, or in other words \(\text{rank}(A)=n\). This happens only when the columns are linearly independent. This relationship between invertibility, linear independence, and rank is important, so make sure you understand it well.

I’ll repeat this once more because it’s important: if a matrix has full column rank, its nullspace contains only the zero vector, which means the associated linear transformation is injective. This fact will become especially important later on when we work with least squares.

The rank of a product of matrices is slightly more interesting. Recall that matrix multiplication can be viewed from two complementary perspectives. Given a product \(AB\), the matrix \(A\) multiplies \(B\) on the left, while \(B\) multiplies \(A\) on the right.

When multiplying on the right, the rows of \(AB\) are linear combinations of the rows of \(B\). This means the row space of \(AB\) is contained in the row space of \(B\), and therefore

\(\text{rank}(AB) \leq \text{rank}(B)\)

Similarly, when multiplying on the left, the columns of \(AB\) are linear combinations of the columns of \(A\). Hence, the column space of \(AB\) is contained in the column space of \(A\), which implies

\(\text{rank}(AB) \leq \text{rank}(A)\)

Putting these observations together, we conclude that

\(\text{rank}(AB) \leq \min(\text{rank}(A), \text{rank}(B))\)

Finally, if a matrix is multiplied by an invertible matrix (on either side), its rank does not change. Invertible transformations preserve all linear information, so no dimensions of the row space or column space are lost.

Summary

- Some transformations cannot be reversed and are therefore not invertible, either because they crush dimensions and lose information, or because they do not cover the whole space.

- Only square matrices can have a true inverse, provided their columns are linearly independent, meaning the column space spans the entire space.

- Rectangular matrices can have partial inverses, in the form of a left inverse or a right inverse.

- The rank of a matrix tells us how much information is lost. It is the dimension of the column space or the row space, and the row rank equals the column rank.

- A matrix is invertible if and only if it has full rank, which means no information is lost.